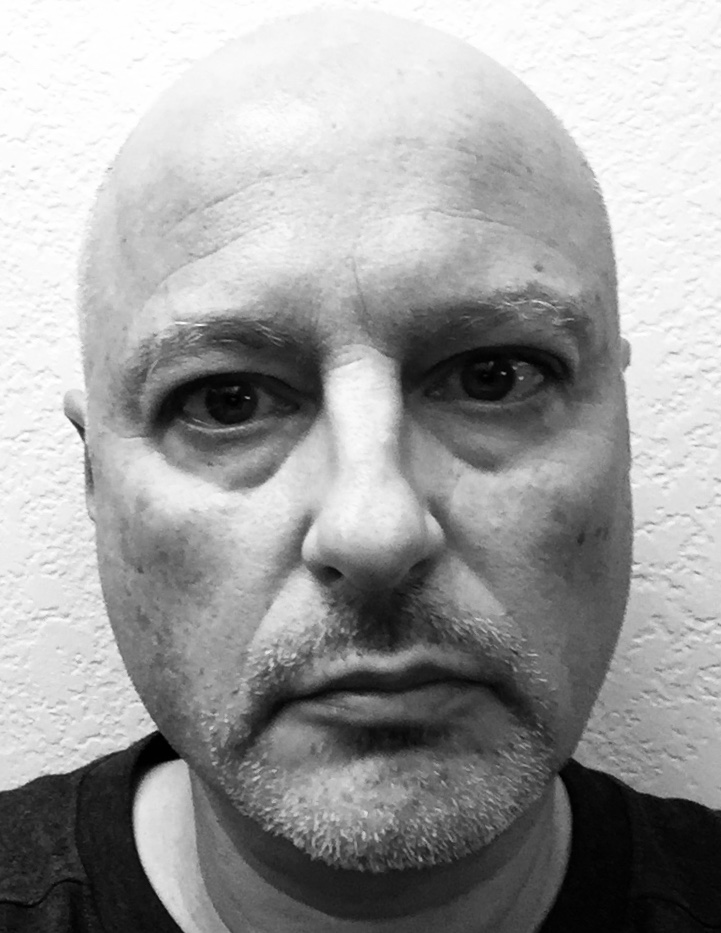

Thomas A. Blackson

Morning, 10/26/2018.

Apparently Socrates

looked

worse.

Philosophy Faculty

Morning, 10/26/2018.

Apparently Socrates

looked

worse.

Philosophy Faculty

Lattie F. Coor Hall, 3356

School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies

Arizona State University

Tempe, AZ. 85287-4302

USA

Email: blackson@asu.edu

curriculum vitae

Intellectual Biography

I was born in Havre de Grace, Maryland. I went to college in the Midwest. When I graduated, I moved to the Boston area because some friends were moving there. I worked in computers, first as a systems analyst at Instrumentation Laboratory in Lexington, later in the Sloan School at MIT. After a few years, I took a PhD in Philosophy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. My first academic jobs were visiting positions. I was a Visiting Assistant Professor for two years at North Carolina State University and then for two years at Arizona State University. My first permanent position was at Temple University as an Assistant Professor. After three years, I was promoted with tenure to Associate Professor. I did not like living in the East. When a job came open at Arizona State University, I took a reduction in rank and returned as an Assistant Professor. I enjoyed living there the first time. The desert in Arizona is beautiful. The sky is open and clear blue, and the sunsets and sunrises are spectacular. Two years later, I was tenured and promoted to Associate Professor for a second time.

Academic Research

Service to the Profession:

Managing Editor, Philosophical Studies, 2011-2020

Book Symposium Editor, Philosophical Studies, 2002-present

Recent Teaching:

PHI 319: Philosophy, Computing, and Artificial Intelligence.

An introduction to logical techniques to model the intelligence of a rational agent.

PHI 328: History of Ancient Philosophy.

An introduction to the philosophical discussion in the Greek and Roman world from 585 BCE to 529 CE.

PHI 333: Introduction to Symbolic Logic.

An introduction to symbolic techniques to represent and evaluate sentences, arguments, and theories.

PHI 420: Topics in the History of Ancient Philosophy.

Hellenistic Epistemology.

PHI 420/581: Studies in Ancient Greek Philosophy.

An investigation into the origin of the notion of free will.

My academic research interests are primarily in Ancient philosophy, although I have

occasionally published work in epistemology and in other areas of contemporary philosophy.

•"Epictetus, the Early Stoics, and Frede’s Argument for the First Notion of a Will"

Rhizomata. A Journal for Ancient Philosophy and Science. 15, 1 (2025), 83-101.

[abstract]

Michael Frede has argued that there is a minimum belief for a Stoic to have a notion of a

will and that Epictetus and the late Stoics were the first to have this belief. Against Frede’s

interpretation, I argue for a new understanding of what the Stoics believed. Epictetus did not

believe, as Frede argues, that adult human beings choose to assent to impulsive impressions.

This gets the object of choice wrong in the minimum belief. He believed that the choice adult

human beings make is to exercise their ability to use their impressions, and I argue that

the early Stoics probably believed this too.

Michael Frede has argued that there is a minimum belief for a Stoic to have a notion of a

will and that Epictetus and the late Stoics were the first to have this belief. Against Frede’s

interpretation, I argue for a new understanding of what the Stoics believed. Epictetus did not

believe, as Frede argues, that adult human beings choose to assent to impulsive impressions.

This gets the object of choice wrong in the minimum belief. He believed that the choice adult

human beings make is to exercise their ability to use their impressions, and I argue that

the early Stoics probably believed this too.

•"Believing for Practical Reasons in Plato's Gorgias"

Rhizomata. A Journal for Ancient Philosophy and Science, 11, 1 (2023), 105-125.

[abstract]

In Plato’s Gorgias, Socrates says to Callicles that “your love of the people,

existing in your soul, stands against me, but if we closely examine these same

matters often and in a better way, you will be persuaded” (513c7-d1). I argue for

an interpretation that explains how Socrates understands Callicles’s love of the

people to stand against him and why he believes examination often and in a

better way will persuade Callicles.

In Plato’s Gorgias, Socrates says to Callicles that “your love of the people,

existing in your soul, stands against me, but if we closely examine these same

matters often and in a better way, you will be persuaded” (513c7-d1). I argue for

an interpretation that explains how Socrates understands Callicles’s love of the

people to stand against him and why he believes examination often and in a

better way will persuade Callicles.

•"Early Thinking about Likings and Dislikings."

Ancient Philosophy Today: DIALOGO, 4, 2 (2022), 176–195.

[abstract]

In Plato’s Protagoras, Socrates argues that "the many" are confused about the

experience they describe as "being overcome by pleasure." They think the cause is

"something other than ignorance." He argues it follows from what they believe that the

cause is "ignorance" and "false belief." I show that his argument depends on a premise

he does not introduce but they should reject: that when someone is overcome by

pleasure, the desire stems from a belief. To explain why Plato does not make Socrates introduce this premise, the account I construct is speculative. It starts from the assumption that Plato is thinking through an understanding of human beings and what they must do to live good lives that he takes the historical Socrates to set out.

In Plato’s Protagoras, Socrates argues that "the many" are confused about the

experience they describe as "being overcome by pleasure." They think the cause is

"something other than ignorance." He argues it follows from what they believe that the

cause is "ignorance" and "false belief." I show that his argument depends on a premise

he does not introduce but they should reject: that when someone is overcome by

pleasure, the desire stems from a belief. To explain why Plato does not make Socrates introduce this premise, the account I construct is speculative. It starts from the assumption that Plato is thinking through an understanding of human beings and what they must do to live good lives that he takes the historical Socrates to set out.

•"Before and After Philosophy Takes Possession of the Soul. The Ascetic

and the Platonic Interpretation."

Journal of Ancient Philosophy, 14, 2 (2020), 53-75.

[abstract]

In the Phaedo, to explain why the philosopher lives in the unusually ascetic way he

does, Socrates explains what someone realizes when philosophy takes possession of

his soul and how he changes his behavior on the basis of this information. This paper

considers the conception of belief the character uses in this explanation and whether

it is the same as the conception Michael Frede thinks the historical Socrates is likely

to have held and that the Stoics much later incorporated into their doctrine of practice.

In the Phaedo, to explain why the philosopher lives in the unusually ascetic way he

does, Socrates explains what someone realizes when philosophy takes possession of

his soul and how he changes his behavior on the basis of this information. This paper

considers the conception of belief the character uses in this explanation and whether

it is the same as the conception Michael Frede thinks the historical Socrates is likely

to have held and that the Stoics much later incorporated into their doctrine of practice.

•"Academic Justifications of Assent"

What the Ancients Offer to Contemporary Epistemology (edited by Stephen

Hetherington and Nicholas D. Smith). Routledge, 2020.

[abstract]

The Clitomachians and the Philonian/Metrodorians responded in different ways

to the challenge the Stoic epistemology posed for the Academic assent to

persuasive impressions. I argue that the Clitomachians did not respond in

terms of the Stoic framework according to which the justification of assent is

a factual property, that the Philonian/Metrodorians did, and that because they

prevailed within the Academy, their response had an important consequence for

the subsequent tradition. It allowed the Stoic conception of justification as

a purely factual matter to enter the tradition without the accompanying

support of the Stoic metaphysics.

•"Plato (ca. 427-ca. 347 B.C.): Apology of Socrates"

AUTOBIOGRAPHY/AUTOFICTION. An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook. Volume

III: Exemplary autobiographical/autofictional texts. Edited by Martina

Wagner-Egelhaaf. De Gruyter, Berlin, 2019. (Submitted 2013.)

[abstract]

I consider the possibility that the Apology is a work of autofiction.

Autofiction is a genre in which the author tries to bring out something

important about a person or a series of events that the author witnessed, but

that the reader would miss in a straightforward historical account. My focus

is on Apology 29c-30b, where Socrates explains what he will not stop

doing.

•"Epicureanism"

The History of Evil,

Volume 1: The History of Evil in Antiquity. 2000 BCE-450 CE (edited by Tom Angier), 163-174.

Routledge, 2018. (Submitted 2012.)

[abstract]

Epicurus did not discuss evil as theological problem. He was interested in the

practical problem of living well, and it is in this connection that Epicurus

made a lasting contribution to understanding evil and its causes. He rejected

the dominate line of thought from the classical tradition of Plato and

Aristotle. Epicurus was an empiricist, not a rationalist. From within this

perspective, he developed a new understanding of the good life.

•"Impulsive Impressions"

Rhizomata. A Journal for Ancient Philosophy and Science, 9 (2017), 91-112.

[abstract]

In the secondary literature, there are two interpretations of how the Stoics

understood impulsive impressions in adults: what I call the "form"

interpretation and the "no-form" interpretation. Brad Inwood and other

historians argue for the form interpretation on the basis of Stobaeus' account

of Stoic ethics. I argue that these arguments are not sound and that the

passages in Stobaeus provide no reason to believe that the form interpretation

is more plausible than the no-form interpretation.

In the secondary literature, there are two interpretations of how the Stoics

understood impulsive impressions in adults: what I call the "form"

interpretation and the "no-form" interpretation. Brad Inwood and other

historians argue for the form interpretation on the basis of Stobaeus' account

of Stoic ethics. I argue that these arguments are not sound and that the

passages in Stobaeus provide no reason to believe that the form interpretation

is more plausible than the no-form interpretation.

•"The Stoic Explanation for the Origin of Vice"

Méthexis: International Journal for Ancient Philosophy, 29 (2017), 121-140.

[abstract]

The Stoics thought that once human beings become rational, they immediately form

false beliefs about what is good and what is bad. There are no exceptions. Even

the sage once had false beliefs about the value of things. The dispute among the

Stoics was not about whether this happens, but was about how to explain the

reasoning that results in these beliefs. The primary evidence for this dispute

is Galen's discussion in On the Doctrines of Plato and Hippocrates. On

the basis of this discussion and certain assumptions about how the Stoics

understood impulses in the psychology of children and adults, I set out an

interpretation of (i) Chrysippus' explanation of what happens at the onset of

reason when human beings form false beliefs about what is good and what is bad,

(ii) Posidonius' criticism of this explanation of the origin of vice, and (iii)

the explanation that Posidonius himself thought was correct.

The Stoics thought that once human beings become rational, they immediately form

false beliefs about what is good and what is bad. There are no exceptions. Even

the sage once had false beliefs about the value of things. The dispute among the

Stoics was not about whether this happens, but was about how to explain the

reasoning that results in these beliefs. The primary evidence for this dispute

is Galen's discussion in On the Doctrines of Plato and Hippocrates. On

the basis of this discussion and certain assumptions about how the Stoics

understood impulses in the psychology of children and adults, I set out an

interpretation of (i) Chrysippus' explanation of what happens at the onset of

reason when human beings form false beliefs about what is good and what is bad,

(ii) Posidonius' criticism of this explanation of the origin of vice, and (iii)

the explanation that Posidonius himself thought was correct.

•"Against Weatherson on How to Frame a Decision Problem."

Journal of Philosophical Research, 41 (2016), 69-72.

[abstract]

In "Knowledge, Bets, and Interests," Brian Weatherson makes a suggestion for how

to frame a decision problem. He argues that "the states we can 'leave off' a

decision table are the states that the agent knows not to obtain." I present and

defend an example that shows that Weatherson's principle is false.

In "Knowledge, Bets, and Interests," Brian Weatherson makes a suggestion for how

to frame a decision problem. He argues that "the states we can 'leave off' a

decision table are the states that the agent knows not to obtain." I present and

defend an example that shows that Weatherson's principle is false.

•"Two Interpretations of Socratic Intellectualism"

Ancient Philosophy, 35 (2015), 23-39.

[abstract]

Among historians of philosophy, Socratic intellectualist psychology has been

understood in at least two ways. On one way (the D interpretation), all

action is a matter of a fixed desire for the good and belief about what the good

is. On another interpretation (the B interpretation), all action is

completely a matter of belief. I argue for the B interpretation of

Socrates' intellectualism in the Protagoras.

Among historians of philosophy, Socratic intellectualist psychology has been

understood in at least two ways. On one way (the D interpretation), all

action is a matter of a fixed desire for the good and belief about what the good

is. On another interpretation (the B interpretation), all action is

completely a matter of belief. I argue for the B interpretation of

Socrates' intellectualism in the Protagoras.

•"On Feldman's Theory of Happiness." Utilitas, 21(2009), 393-400.

[abstract]

In Pleasure and the Good Life (OUP, 2004), Fred Feldman argues that

there is a propositional attitude (he calls "attitudinal pleasure/displeasure")

expressed in ordinary uses of sentences of the form 'S is pleased/displeased

that P.' He distinguishes intrinsic from extrinsic attitudinal

pleasure and displeasure, and he excludes extrinsic attitudinal

pleasure/displeasure from the aggregation of attitudinal pleasure/displeasure

that constitutes happiness. I argue that Feldman has not made a strong case for

this distinction and exclusion.

In Pleasure and the Good Life (OUP, 2004), Fred Feldman argues that

there is a propositional attitude (he calls "attitudinal pleasure/displeasure")

expressed in ordinary uses of sentences of the form 'S is pleased/displeased

that P.' He distinguishes intrinsic from extrinsic attitudinal

pleasure and displeasure, and he excludes extrinsic attitudinal

pleasure/displeasure from the aggregation of attitudinal pleasure/displeasure

that constitutes happiness. I argue that Feldman has not made a strong case for

this distinction and exclusion.

•"On Williamson's Argument for (Ii) in his Anti-luminosity Argument."

Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 74 (2007), 397-405.

[abstract]

Williamson's anti-luminosity argument depends on what he says is an "intuitive"

connection between knowledge and reliability. (Knowledge and its Limits

(OUP, 2000), 100.) I believe that the connection is "intuitive," although this

can take some time to see, but I argue that this "intuitive" connection is not

sufficient to support (Ii) in his anti-luminosity argument.

Williamson's argument against luminosity is not sound.

Williamson's anti-luminosity argument depends on what he says is an "intuitive"

connection between knowledge and reliability. (Knowledge and its Limits

(OUP, 2000), 100.) I believe that the connection is "intuitive," although this

can take some time to see, but I argue that this "intuitive" connection is not

sufficient to support (Ii) in his anti-luminosity argument.

Williamson's argument against luminosity is not sound.

•"In Defense of an Unpopular Interpretation of Ancient Skepticism."

Logical Analysis and the History of Philosophy: History of Epistemology, 8 (2005), 68-81.

[abstract]

The subject of this paper is the history of late Academic Skepticism and its

connection to the emergence of Pyrrhonian Skepticism. The two main ways to

understand this period in history are anthologized in The Original Sceptics:

A Controversy (Hackett Publishing Company, 1977), edited by Myles Burnyeat

and Michael Frede. To many, Frede's position has been less convincing to many

than Burnyeat's. Frede argues that life without belief was not a fundamental

feature of Pyrrhonism. Frede presents his arguments somewhat confusingly, which

has made his interpretation difficult to appreciate, but I argue that there is

more to be said for Frede's interpretation than has been thought. I argue that

Frede's interpretation, when properly understood, shows that the ancient

skeptics in the Clitomachian-Pyrrhonian tradition are fallibilists who took the

first steps in working out the view that epistemic justification is a matter of

whether a belief is the outcome of a correct cognitive process and that

correctness here need not be understood in terms of a reliable connection to

truth.

The subject of this paper is the history of late Academic Skepticism and its

connection to the emergence of Pyrrhonian Skepticism. The two main ways to

understand this period in history are anthologized in The Original Sceptics:

A Controversy (Hackett Publishing Company, 1977), edited by Myles Burnyeat

and Michael Frede. To many, Frede's position has been less convincing to many

than Burnyeat's. Frede argues that life without belief was not a fundamental

feature of Pyrrhonism. Frede presents his arguments somewhat confusingly, which

has made his interpretation difficult to appreciate, but I argue that there is

more to be said for Frede's interpretation than has been thought. I argue that

Frede's interpretation, when properly understood, shows that the ancient

skeptics in the Clitomachian-Pyrrhonian tradition are fallibilists who took the

first steps in working out the view that epistemic justification is a matter of

whether a belief is the outcome of a correct cognitive process and that

correctness here need not be understood in terms of a reliable connection to

truth.

•"An Invalid Argument for Contextualism."

Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 68 (2004), 344-345.

[abstract]

In "Assertion, Knowledge, and Context" (Philosophical Review, Vol. 111,

No. 2 (April 2002), 167-203), Keith DeRose argues for contexualism as follows.

"The knowledge account assertion provides a powerful argument for contextualism:

if the standards for when one is in a position to warrantedly assert that P are

the same as those what comprise a truth-condition for 'I know P,' then if the

former vary with context, so do the latter. In short: The knowledge account of

assertion together with the context-sensitivity of assertability yields

contextualism about knowledge" (187). I show that this argument is invalid.

In "Assertion, Knowledge, and Context" (Philosophical Review, Vol. 111,

No. 2 (April 2002), 167-203), Keith DeRose argues for contexualism as follows.

"The knowledge account assertion provides a powerful argument for contextualism:

if the standards for when one is in a position to warrantedly assert that P are

the same as those what comprise a truth-condition for 'I know P,' then if the

former vary with context, so do the latter. In short: The knowledge account of

assertion together with the context-sensitivity of assertability yields

contextualism about knowledge" (187). I show that this argument is invalid.

According to the Stoics, human beings enslave themselves. When they change from

nonrational children into rational adults, they form false beliefs about what is

good and what is bad. These beliefs enslave them to things that are neither good

nor bad. I argue for an interpretation of how the Stoics understood the

reasoning that results in these false beliefs. This interpretation helps makes

sense of the argument against Chrysippus's explanation of the origin of vice

that Galen attributes to Posidonius. It also helps explain how the Stoics could

think that nature is provident and that nature constructs human beings so that

they enslave themselves when they change from nonrational children into rational

adults.

According to the Stoics, human beings enslave themselves. When they change from

nonrational children into rational adults, they form false beliefs about what is

good and what is bad. These beliefs enslave them to things that are neither good

nor bad. I argue for an interpretation of how the Stoics understood the

reasoning that results in these false beliefs. This interpretation helps makes

sense of the argument against Chrysippus's explanation of the origin of vice

that Galen attributes to Posidonius. It also helps explain how the Stoics could

think that nature is provident and that nature constructs human beings so that

they enslave themselves when they change from nonrational children into rational

adults. I argue for an alternative interpretation of some of the examples Fred Feldman

uses to establish his theory of happiness (in Pleasure and the Good

Life (OUP, 2004) and What is This Thing Called Happiness?

(OUP,2010)). According to Feldman, the examples show that certain utterances of

the form 'S is pleased/glad that P' and 'S is displeased/sad that P' should be

interpreted as expressions of extrinsic attitudinal pleasure and displeasure and

hence must be excluded from the aggregative sum of attitudinal pleasure and

displeasure that constitutes happiness. I develop a new interpretation of

Feldman's examples. This interpretation allows the attitudinal hedonist to

preserve the idea that happiness is simply a matter of the attitudinal pleasure

and displeasure in one's life and that all attitudinal pleasure and displeasure

counts equally in the aggregation that constitutes happiness.

I argue for an alternative interpretation of some of the examples Fred Feldman

uses to establish his theory of happiness (in Pleasure and the Good

Life (OUP, 2004) and What is This Thing Called Happiness?

(OUP,2010)). According to Feldman, the examples show that certain utterances of

the form 'S is pleased/glad that P' and 'S is displeased/sad that P' should be

interpreted as expressions of extrinsic attitudinal pleasure and displeasure and

hence must be excluded from the aggregative sum of attitudinal pleasure and

displeasure that constitutes happiness. I develop a new interpretation of

Feldman's examples. This interpretation allows the attitudinal hedonist to

preserve the idea that happiness is simply a matter of the attitudinal pleasure

and displeasure in one's life and that all attitudinal pleasure and displeasure

counts equally in the aggregation that constitutes happiness. I wrote this book to solve a problem. It seemed to me, when I was teaching

ancient philosophy, that my students did not want to spend all their time taking

notes. They wanted to listen and think about the material, and they wanted to

take part in a discussion. For this to be possible, they must have some

understanding of the material prior to class. The problem is how to give the

students this understanding. The standard scholarly works provide the wrong kind

of explanation for beginning students. These works are narrowly focused on a

period within the history or on a specific text. Beginning students find such

detailed analysis and argument difficult to comprehend because so much of it

presupposes a general understanding of the historical figures and lines of

thought that define the ancient philosophical tradition. The standard

anthologies are the traditional alternative, but they do not provide enough

explanation for beginning students. They provide brief introductory remarks, and

these remarks are almost always too brief to provide the understanding beginning

students need. What students need is an explanation of the lines of thought that

define ancient philosophy and in terms of which it develops. This is what I try

to provide.

I wrote this book to solve a problem. It seemed to me, when I was teaching

ancient philosophy, that my students did not want to spend all their time taking

notes. They wanted to listen and think about the material, and they wanted to

take part in a discussion. For this to be possible, they must have some

understanding of the material prior to class. The problem is how to give the

students this understanding. The standard scholarly works provide the wrong kind

of explanation for beginning students. These works are narrowly focused on a

period within the history or on a specific text. Beginning students find such

detailed analysis and argument difficult to comprehend because so much of it

presupposes a general understanding of the historical figures and lines of

thought that define the ancient philosophical tradition. The standard

anthologies are the traditional alternative, but they do not provide enough

explanation for beginning students. They provide brief introductory remarks, and

these remarks are almost always too brief to provide the understanding beginning

students need. What students need is an explanation of the lines of thought that

define ancient philosophy and in terms of which it develops. This is what I try

to provide. In The Brute Within (OUP, 2006), Hendrik Lorenz tries to incorporate

Plato's Tripartite Theory of the Soul within the framework of the ancient

Rationalist/Empiricist tradition that Michael Frede outlined in a series of

papers. To correct what I believe is a mistake in Lorenz's interpretation, I

consider certain passages in the Gorgias in which Socrates discusses

the kind of cognition he calls "experience." I argue that these passages

strongly suggest that Plato, in the Republic, in the Tripartite Theory,

allows for action to be completely a matter of the appetite and spirit, with

reason playing no role whatsoever. Further, given my interpretation of the

Tripartite Theory, I note that there is a clear connection between Plato's work

in understanding the Socratic claim that human beings are psychological beings

and contemporary work in philosophical psychology according to which cognitive

behavior can be rational even though no part of this behavior depends on an

instance of reasoning. Plato was the pioneer in the development of this idea,

and Lorenz's interpretation unnecessarily obscures this fact.

In The Brute Within (OUP, 2006), Hendrik Lorenz tries to incorporate

Plato's Tripartite Theory of the Soul within the framework of the ancient

Rationalist/Empiricist tradition that Michael Frede outlined in a series of

papers. To correct what I believe is a mistake in Lorenz's interpretation, I

consider certain passages in the Gorgias in which Socrates discusses

the kind of cognition he calls "experience." I argue that these passages

strongly suggest that Plato, in the Republic, in the Tripartite Theory,

allows for action to be completely a matter of the appetite and spirit, with

reason playing no role whatsoever. Further, given my interpretation of the

Tripartite Theory, I note that there is a clear connection between Plato's work

in understanding the Socratic claim that human beings are psychological beings

and contemporary work in philosophical psychology according to which cognitive

behavior can be rational even though no part of this behavior depends on an

instance of reasoning. Plato was the pioneer in the development of this idea,

and Lorenz's interpretation unnecessarily obscures this fact.